Cloud cost monitoring is often one of the first cost-related capabilities teams put in place as cloud usage grows. They start with enabling billing exports, setting up dashboards, and configuring alerts to make sure their spend is visible across services and accounts. With this level of insight, it’s natural to assume that cloud costs are finally “under control.”

Yet in many cases, improved visibility does not translate into lower costs. Despite better visibility, the overall cloud spend continues to rise.

This gap exists because cloud cost monitoring and cloud cost control are not the same thing, even though they are frequently treated as interchangeable. Monitoring focuses on observation like collecting billing data, tracking usage trends, and answering questions about where money is going. Cost control, on the other hand, is fundamentally different. It involves making decisions (often under uncertainty) that directly influence how infrastructure is provisioned, committed, and constrained over time.

The distinction matters because cloud costs are not caused by a single misconfiguration or runaway service. They are the cumulative result of architectural choices, scaling behavior, pricing models, and time-based commitments.

This article breaks down the practical difference between cloud cost monitoring and cloud cost control, why monitoring alone rarely leads to sustained savings, and where teams typically run into friction when they try to move from visibility to action.

Cloud cost monitoring is the process of collecting, aggregating, and visualizing cloud billing and usage data to understand how money is being spent over time. It answers descriptive questions such as how much was spent, where the spend came from, and how it has changed.

Most cloud platforms expose detailed billing data through native cost and usage reports. Cloud cost monitoring systems evaluate this data, normalize it, and present it in forms that are easier to analyze, like dashboards, charts, alerts, and reports.

While implementations vary, most cloud cost monitoring setups rely on a similar set of technical building blocks:

Together, these components provide a detailed picture of what is happening financially inside a cloud environment.

Cloud cost monitoring excels at retrospective analysis. It is well suited for:

In other words, monitoring turns cloud spend into observable data that can be queried, analyzed, and discussed.

What cloud cost monitoring does not do is enforce behavior or make decisions. It does not change how resources are provisioned, prevent inefficient usage patterns, or determine whether future commitments should be made. Even when alerts fire or dashboards show clear inefficiencies, monitoring systems typically stop at notification.

Understanding that boundary is critical, because many of the largest cloud savings opportunities are not driven by reacting to past usage, but by making forward-looking decisions about how infrastructure should be priced, constrained, or committed going forward.

Also read: Why Cloud Resource Optimization Alone Doesn’t Fix Cloud Costs

Cloud cost control is about placing constraints on cloud usage and pricing behavior. These constraints can be financial, architectural, or policy-driven, and they are designed to limit unnecessary spend while preserving required functionality and performance.

In other words, while cloud cost monitoring focuses on understanding spend after it happens, cloud cost control is concerned with influencing spend before it occurs.

Cloud cost control relies on a different set of mechanisms than monitoring. Instead of dashboards and alerts, it introduces systems that affect provisioning and pricing decisions directly. Common control mechanisms include:

Each of these mechanisms directly affects future spend. Unlike monitoring, which is passive by design, cost control systems actively change how infrastructure behaves.

The complexity of cost control stems from the fact that it is predictive rather than retrospective. Decisions must be made based on assumptions about future usage, growth, and stability. If those assumptions are wrong, the impact becomes financial.

This introduces several challenges:

Some control decisions, particularly pricing commitments, cannot be undone immediately.

Also read: Why Cloud Cost Management Keeps Failing (and What Teams Are Missing)

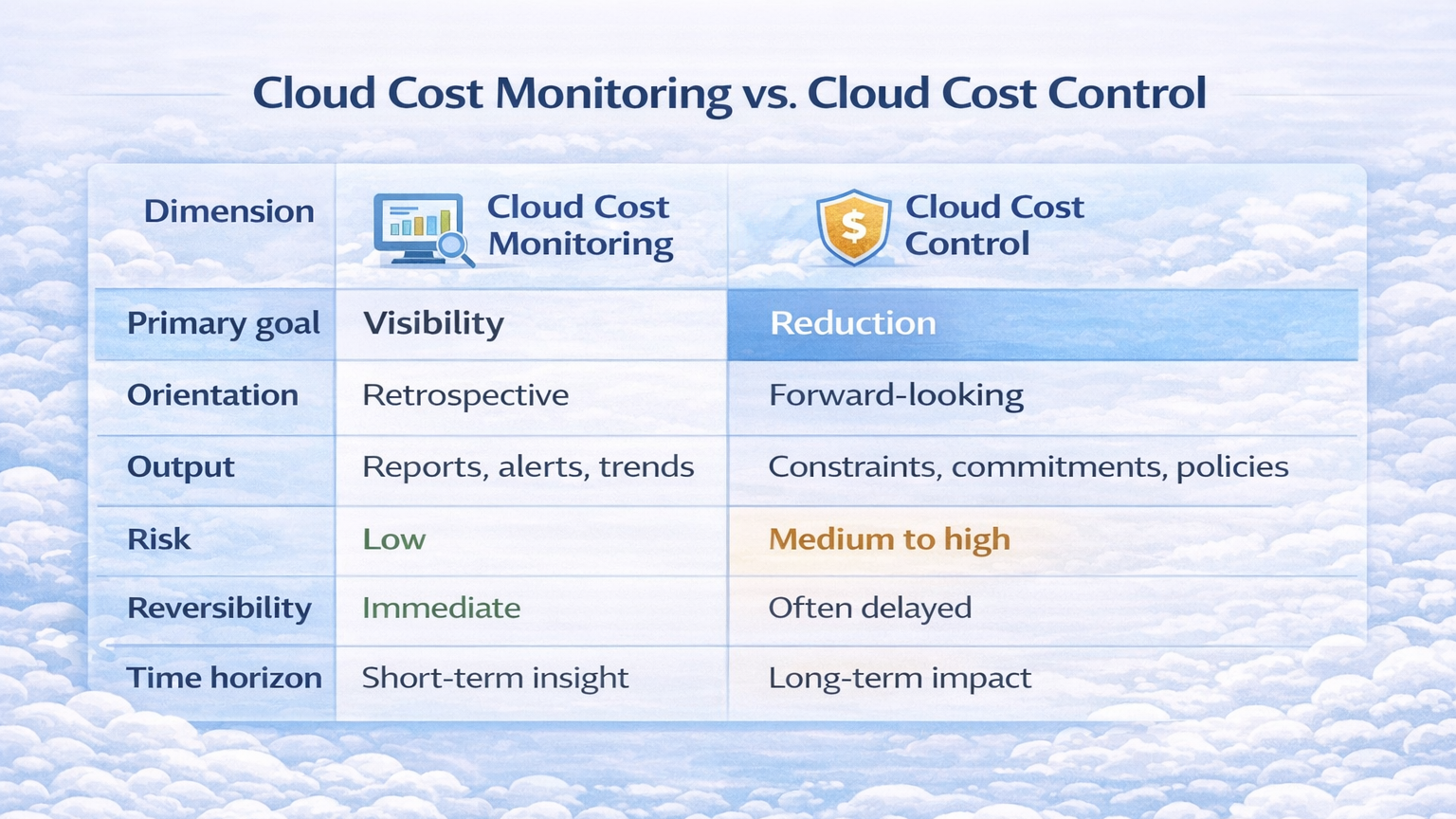

At a high level, cloud cost monitoring is descriptive, while control is prescriptive. That distinction has practical consequences for how each is implemented and how much risk it introduces.

Cloud cost monitoring is built around data flow. Usage and billing data move from the cloud provider into reporting systems, where they are aggregated, analyzed, and visualized. The output is information with charts, trends, alerts, and reports.

Cloud cost control introduces a decision flow. Information from monitoring systems feeds into rules, policies, or commitment decisions that actively influence how infrastructure behaves going forward. Once those decisions are applied, they shape future spend regardless of what monitoring tools report afterward.

This difference explains why monitoring systems tend to be additive and non-invasive, while control mechanisms are often embedded deeper into provisioning, governance, or financial processes.

Cloud cost monitoring is inherently low-risk. If a dashboard is misconfigured or an alert is noisy, the consequence is usually inconvenience rather than financial loss. Monitoring failures are visible and reversible.

Cost control carries a higher risk profile. Decisions such as enforcing budgets, restricting resource types, or committing to discounted pricing are based on assumptions about future usage. If those assumptions change, the impact can persist over time. In some cases, control decisions are difficult or expensive to reverse.

This asymmetry is one reason organizations often invest heavily in monitoring long before they are comfortable with control.

Cloud cost monitoring looks backward. Even when it operates close to real time, it is fundamentally retrospective and it explains what has already occurred.

Cost control looks forward. It operates on expectations about workload stability, growth, and architectural direction. The benefits of control mechanisms often materialize over weeks or months, not immediately.

As a result:

Cloud cost monitoring creates visibility, but visibility alone does not change system behavior. This is the core reason many organizations see improved reporting without seeing a corresponding decrease in spend. The mechanisms that surface cost data are fundamentally different from the mechanisms that influence how costs are incurred.

Monitoring systems are designed to observe and report. They surface information after usage has already occurred, for example, which services were used, how much they cost, and how those costs changed over time. By the time a cost spike appears on a dashboard or triggers an alert, the underlying consumption has already happened.

Reducing cloud spend, however, requires intervening earlier in the lifecycle, at provisioning time, scaling time, or pricing decision time. Monitoring highlights inefficiencies, but it does not resolve them unless something downstream acts on that information.

Cost issues accumulate quietly. A 5–10% inefficiency rarely causes an immediate failure, even though it can translate into significant spend over time.

Because cost problems are slow-moving, they are easy to deprioritize. Monitoring tools may surface trends and anomalies, but without a forcing function, those insights compete with reliability, feature delivery, and operational work.

Even when monitoring systems provide accurate attribution, clearly showing which service, workload, or team is responsible for spend, that clarity does not automatically enable reduction.

Attribution answers who and where, but not what should change. Many cost drivers are structural:

Monitoring can expose these patterns, but it does not resolve the underlying tradeoffs.

In most setups, cost monitoring outputs feed into human decision-making loops. Dashboards are reviewed periodically, alerts are triaged, and recommendations are discussed. This process introduces several sources of friction:

These frictions compound over time, reducing the likelihood that monitoring insights lead to sustained changes.

Perhaps the most important limitation is that cloud cost monitoring is inherently retrospective. Even near–real-time estimates are based on usage that has already occurred. The largest savings opportunities in cloud pricing, such as discounted rates tied to commitments are forward-looking by nature.

Decisions about pricing models, baseline capacity, and long-term usage assumptions cannot be made purely by looking backward. They require confidence in future behavior and a willingness to accept tradeoffs.

Also read: How to Cut Cloud Spend Without Taking Commitment Risk

Among all cost control techniques, pricing commitments consistently offer the largest potential savings and also introduce the most hesitation. Unlike reactive controls such as alerts or schedules, commitments change the unit economics of cloud usage itself.

Cloud pricing commitments work by exchanging flexibility for lower rates. In return for committing to a certain level of usage or spend over a fixed period, the provider offers a discounted price compared to on-demand rates. The discount applies automatically as usage accrues, reducing cost without changing how workloads are provisioned or scaled.

From a systems perspective, commitments:

This is why commitments often account for the majority of achievable savings in mature cloud environments.

While implementations differ, most commitment models share similar characteristics:

These commitment models vary in duration, scope, and flexibility, but they all introduce long-lived pricing assumptions that directly affect future cloud spend.

Commitments align well with how many production systems behave in practice. Most environments have a baseline level of steady demand, like core services, always-on workloads, and predictable traffic floors. For this portion of usage, paying on-demand rates is unnecessarily expensive.

Because commitments do not require changes to application code, scaling logic, or deployment workflows, they are often seen as a “clean” optimization lever. Once in place, they operate invisibly in the background.

The risk of commitments comes from their assumptions. Commitments are made based on expectations about future usage. When those expectations hold, savings are straightforward. When they do not, the discount no longer compensates for the unused portion of the commitment.

Common sources of mismatch include:

In these cases, the unused portion of a commitment becomes a sunk cost.

A key concept in commitment-based cost control is coverage, which is the proportion of total usage that is effectively priced at the discounted rate. Higher coverage generally means lower average cost, but also higher exposure to underutilization if usage drops.

This creates a balancing act:

Finding the right coverage level requires continuously aligning commitments with actual system behavior over time.

Despite the savings potential, many organizations deliberately underutilize commitments. The hesitation is rational. Commitments shift risk from the provider to the customer, and that risk is felt most acutely when systems change faster than pricing terms allow.

From an engineering standpoint, commitments can feel like a constraint on future design choices. From a financial standpoint, they introduce exposure that is difficult to unwind quickly.

This tension explains why commitments are both the most powerful and the most controversial cost control mechanism and why they sit at the center of most cloud cost optimization strategies.

As cloud environments grow in scale and complexity, AI and automation are often positioned as the solution to cost management challenges. Understanding what AI actually does in cloud cost monitoring and control helps set realistic expectations.

Where AI Is Commonly Used Today

Most AI applications in cloud cost tooling focus on pattern detection and recommendation, rather than decision-making or enforcement.

Common uses include:

In all of these cases, AI operates large volumes of cost and usage data more efficiently than humans, surfacing insights that might otherwise be missed.

Despite frequent marketing claims, AI rarely takes responsibility for financial outcomes. Most systems stop at recommendations and require human approval to proceed. They do not:

While AI can improve signal quality, it does not eliminate the uncertainty inherent in forward-looking cost decisions.

It’s also useful to distinguish between automation and autonomy. Many cost tools automate parts of the workflow, like data collection, cost analysis, and reporting, but they stop short of autonomous action. Fully autonomous cost control would require systems to make irreversible financial commitments based on probabilistic forecasts, a step most organizations are not comfortable taking without safeguards.

This explains why AI-driven cost systems tend to be conservative. They are designed to assist decision-making, not replace it.

In practice, AI is most effective when it reduces cognitive load:

When paired with appropriate control mechanisms, AI can make cost management more scalable. On its own, however, it does not close the gap between insight and outcome.

The natural question that follows is what a system looks like when it is designed to bridge this gap end-to-end, rather than stopping at insight or recommendation.

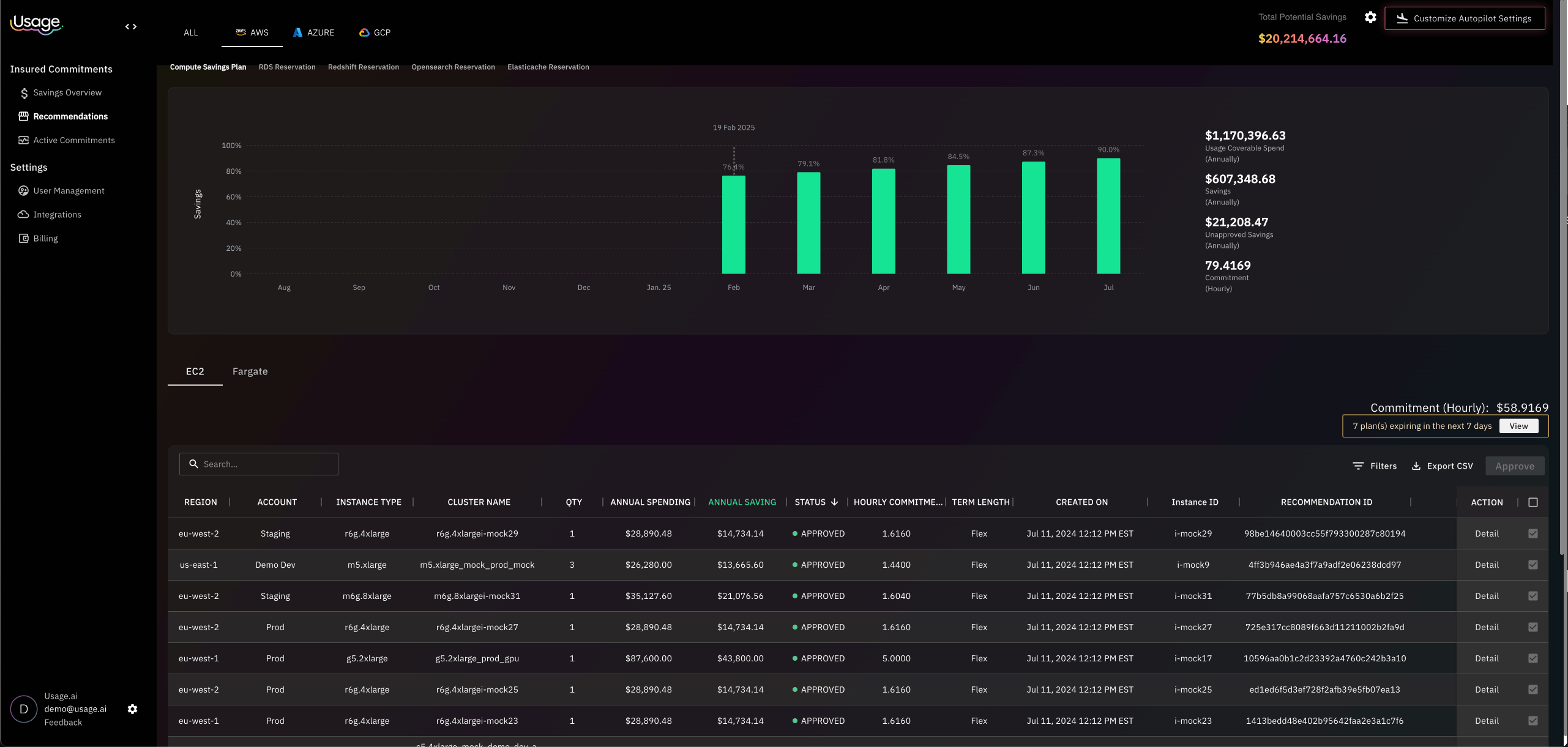

One example of such an approach is Usage.ai, which is built around the idea that cost monitoring data should directly inform automated, forward-looking decisions, while also accounting for the risk those decisions introduce.

In practice, Usage.ai starts from the same raw inputs as traditional monitoring tools that offer cloud billing and usage data collected from provider APIs. The difference lies in what happens next.

Instead of treating monitoring as the end state, cost signals are used to continuously evaluate commitment coverage, like how much of current and projected usage is priced at discounted rates versus on-demand rates. This shifts the focus from explaining past spend to assessing whether current pricing assumptions still align with how systems are actually behaving.

Because usage patterns change, this evaluation needs to be refreshed frequently. Otherwise, recommendations quickly become stale and lose relevance.

A key distinction in this execution model is that commitment decisions are not left entirely manual. Once coverage gaps are identified, the system can propose concrete actions, such as increasing or adjusting commitment levels based on observed usage patterns rather than static forecasts.

Underutilization is the primary reason organizations hesitate to rely more heavily on commitments.

Usage.ai addresses this by pairing automated commitment execution with a cashback protection program that compensates for underutilized commitments under defined conditions. Rather than treating underutilization purely as a customer problem, part of that risk is absorbed by the platform itself.

From a systems perspective, this changes the economics of cost control. It allows higher commitment coverage without requiring perfect forecasts or static architectures, acknowledging that cloud environments evolve.

If you want to see applied to your environment, sign up for free.

1. What is cloud cost monitoring?

Cloud cost monitoring is the practice of collecting and analyzing cloud billing and usage data to understand how much is being spent, where the spend originates, and how it changes over time. It focuses on visibility through dashboards, reports, and alerts rather than enforcing cost reductions.

2. Is cloud cost monitoring the same as cloud cost management?

No. Cloud cost monitoring is a subset of cloud cost management. Monitoring provides visibility into spend, while cost management also includes budgeting, optimization, governance, and decision-making mechanisms that actively influence future costs.

3. Can cloud cost monitoring reduce cloud costs?

On its own, cloud cost monitoring rarely reduces costs. It helps identify inefficiencies and trends, but cost reduction requires additional actions such as enforcing policies, adjusting architectures, or committing to discounted pricing models.

4. Why do cloud costs keep increasing even with good monitoring?

Cloud costs often increase because monitoring is retrospective. It explains what already happened but does not change how infrastructure is provisioned or priced going forward. Structural cost drivers, such as pricing models, baseline capacity, and long-term usage patterns remain unchanged without cost control mechanisms.

5. What role does AI play in cloud cost monitoring?

AI is commonly used for anomaly detection, forecasting, and generating optimization recommendations. It improves signal quality and prioritization, but it typically does not make irreversible financial decisions or guarantee realized savings.

6. How do teams move from monitoring to actual cost savings?

Teams move from monitoring to savings by introducing execution mechanisms that act on cost insights. This usually involves combining monitoring data with policies, automation, or commitment strategies that influence future spend rather than only reporting on past usage.

Share this post